Turkey violence: How dangerous is instability?

- 4 hours ago

- Europe

Turkey's biggest cities, Ankara and Istanbul, have been hit by a spate of deadly bombings. The latest, targeting crowded bus stops in the heart of the capital, has hit Turkey at a moment of high tension.

For so long a beacon of stability between Europe and the Middle East, Turkey is fighting Kurdish militants in its restive east and struggling to prevent violence spreading from across its border with Syria.

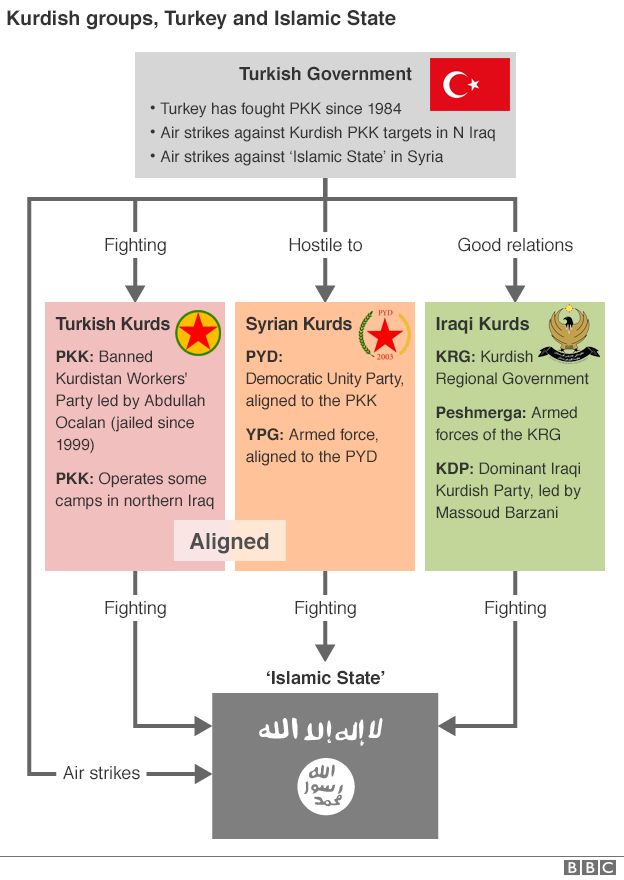

While they see Kurdish militants as the principal threat, Turks have also come under attack from so-called Islamic State (IS).

How dangerous is the current crisis?

AFP

AFP

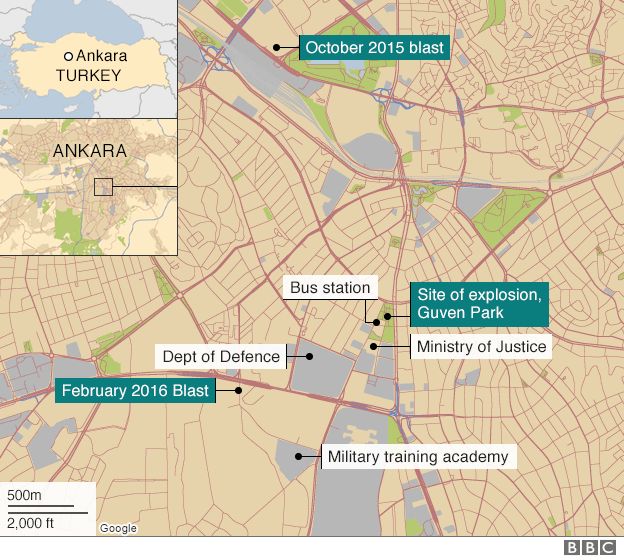

Three atrocities in the centre of Ankara in five months have sent Turks a clear message that nowhere is immune from the violence and that they are being targeted on several fronts.

- The latest atrocity, claimed by Kurdish militant group TAK, hit civilians at a transport hub close to Turkey's justice ministry and the prime minister's office

- Military buses were targeted a short distance away on 17 February and 29 people died. Among the victims were staff streaming out of government offices after work. The attack was also claimed by the TAK, a hardline offshoot of the militant PKK

- More than 100 people died outside Ankara railway station in October 2015. Militants from so-called Islamic State (IS) were blamed for the double bombing, a stone's throw from the headquarters of the national intelligence organisation

Until now, the bloodshed was largely confined to the mainly Kurdish areas of the east and south-east, where the Turkish military has battled the militant Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) for decades.

Violence in the main cities tended to target party offices, particularly those of the left-wing and pro-Kurdish HDP (Peoples' Democratic Party). The banned Marxist DKHP-C has periodically carried out attacks on police and Western embassies.

But now it is Turkish civilians in the heart of Ankara and tourists in Istanbul who are becoming caught up in bombings carried out by Islamists and Kurdish militants. At least 10 people, mainly German visitors, were killed on 12 January, by an IS bomber who blew himself up in the centre of Istanbul's Sultanahmet tourist area.

For millions of tourists every year, Turkey remains an attractive, safe destination, but France has urged its citizens to exercise great vigilance in tourist areas and the UK has warned that "further attacks could be indiscriminate and could affect places visited by foreigners".

AFP

AFP

Turks themselves have become afraid of going to shopping centres and open spaces.

"I think we are seeing a downward spiral towards more violence," warns Prof Menderes Cinar of Baskent University in Ankara.

Turkey's tensions: Read more

- Who are the Kurds? - The long history of the Middle East's fourth-largest ethnic group

- Turkey v Islamic State v the Kurds - What's going on?

- What is 'Islamic State'? - A profile of the militant group

- Border tensions: Why is Azaz in Syria so important for Turkey and the Kurds?

Why has security worsened in Turkey?

Turkey has become embroiled in a conflict on two fronts, inside Turkey and across its Syrian border.

The government in Ankara has for decades fought an internal war with the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party). For two years a ceasefire kept a lid on skirmishes between Turkey and the Kurdish militants, seen as a terrorist group domestically and by much of the West.

But that ceasefire came to an end in July 2015, after a bombing that killed 32 young Kurdish and left-wing activists in the south-eastern city of Suruc.

Those targeted, apparently by an IS bomber, were planning to travel into northern Syria to help rebuild Kobane, a town devastated by IS militants. It was a clear sign that the Syrian conflict had reached Turkey.

A wave of militant attacks and military counter-attacks began, as the PKK accused Turkey of wanting IS fighters to succeed in an attempt to put a stop to Kurdish territorial gains in Syria and Iraq.

"[President] Erdogan is behind IS massacres. His aim is to stop the Kurdish advance against them," PKK leader Cemil Bayik told the BBC last year.

Turkey has imposed curfews on towns and cities in the south-east, in its hunt for Kurdish militants. Turkey and the PKK appear to be back where they were before the 2013 truce began.

AP

APBut why are the main cities coming under attack?

Until now, the PKK carried out much of the violence against government and military targets in the south-east. But its offshoot, the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK), is more hardline and its attacks have become more deadly and more focused on Ankara and Istanbul.

The TAK had been quiet for a few years but renewed conflict in the south-east because of the failed ceasefire has revived the group, says BBC Turkey correspondent Mark Lowen.

Turkey's government does not differentiate between the PKK and its hardline offshoot, arguing that there is a crossover of personnel. The March bombing in the centre of Ankara lends that theory credence as the government says the bomber joined the PKK and was trained over the border in Syria.

Why is the Syrian conflict to blame?

Turkey has long been caught up in the Syrian conflict, and its leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan was among the first to champion rebel opposition groups and call openly for President Bashar al-Assad's removal.

But Turkey has become increasingly concerned about attempts by Kurdish groups to mark out areas of northern Syria under their own control. It fears the rise of the Syrian Kurdish Popular Protection Units (YPG) militia as well as its political arm, the Democratic Union Party (PYD).

"Turkey is feeling a very serious existential threat from the PYD and PKK," says Burhanettin Duran, executive director of Turkey's pro-government Seta research institute. "It's a very solid fact that the PYD and the PKK are the same."

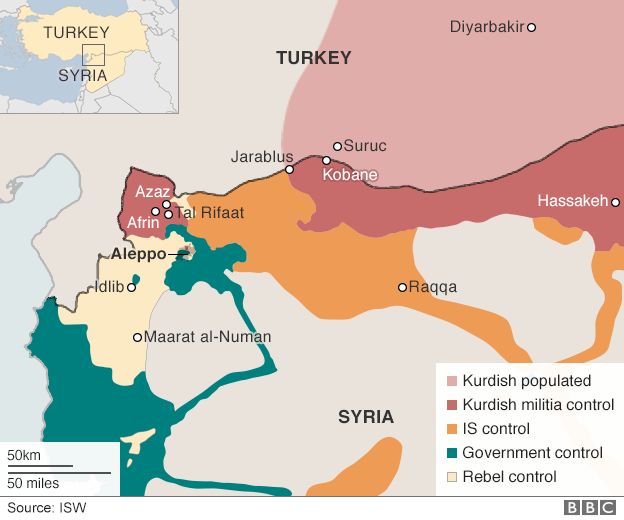

In 2014, three autonomous administrations were declared. Then the YPG beat back IS from the Turkish border in 2015 and established control over a stretch along the border estimated at up to 400km (250 miles) in length.

When Russia intervened in the Syrian conflict in September, the Syrian Kurds found common cause with the advancing Syrian army and its Russian allies and made territorial gains north of Aleppo. Now Syria's Kurds have declared their own federal system.

Kurdish groups now control most of the Syrian border with Turkey, with only a 100km (60-mile) stretch remaining from Azaz to the IS-held town of Jarablus, says the BBC's Selin Girit.

"The state is very suspicious of Kurdish activities on our border, which are against our national interest," says Turkish political commentator Fehmi Koru.

Part of the problem for Turkey, a Nato member, is that while the US sees the PKK as a terrorist group, it backs the Kurdish YPG over the border in Syria.

Can Turkey bring the violence to an end?

There seems little chance of reviving the peace process with the PKK that was launched by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan while he was prime minister.

Turkey's immediate response to the string of bombings has been to target PKK militants and their bases both inside Turkey and across the border in northern Iraq.

"The government has a huge popular mandate and can justify very successfully the end of the peace process," says Prof Cinar.

The answer to the crisis may lie in Syria, where a ceasefire has brought relative calm in areas controlled by the YPG.

Turkey's main goal there will be to stop Kurdish groups bringing together two areas under their control in the north and north-east of Syria.

So far the security forces have been unsuccessful at preventing the bombers from breaching security and Turks fear attacks from the PKK and its affiliates as much as they do from so-called Islamic State.

No comments:

Post a Comment