Greek election 2015: everything you need to know

The parties, the issues, the polls: a complete guide to Greece’s third big national vote of 2015

After months of bruising negotiations with the country’s international creditors, Greece’s newly installed but already-outgoing prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, was forced this summer to accept the draconian terms of a new €85bn (£60bn), three-year bailout.

With the country staring bankruptcy in the face, parliament in Athens approved the package, Greece’s third rescue deal in five years. Nearly a third of the 149 MPs in Tsipras’s leftist Syriza party refused to back him and the 41-year-old prime minister resigned, triggering Greece’s fifth general election in six years.

How did we get here?

Greece was forced to ask for international help when it ran off a fiscal cliff in 2010. After joining the euro in 2001 and gorging for a decade on cheap money, it found itself technically bankrupt.

Greece has received more than €300bn of international bailouts. But these came with strict terms attached: a series of brutal austerity programmes entailing deep budget cuts and steep tax increases.

Greece’s economy has nosedived: GDP has shrunk by 25% since 2010. Nearly 26% of the workforce are unemployed (most of whom do not receive benefits); wages are down 38%, pensions by 45%. Some 18% of the population cannot meet their food needs and 32% live below the poverty line.

Since most of the bailout funds have gone to pay off the country’s loans, almost nothing has been invested in economic recovery. And above all, Greece’s debt mountain is now almost twice the country’s annual economic output – 180% of GDP.

In January’s elections Greece’s exhausted voters finally lost patience with the traditional parties of power. Promising to tear up bailout agreements that had created a “humanitarian crisis”, Syriza surged to a resounding victory.

What are the issues – and what’s likely to happen?

Two months ago Tsipras was riding high on a 70% approval rating as the only Greek prime minister to at least try to stand up to Greece’s lenders. Polls now show support for Syriza among the 18- to 44-year-olds who helped propel it to power has all but collapsed and many of the 62% of Greeks who voted against the new bailout in a referendum in July are bitterly resentful of a party that accepted a deal it had promised to torpedo.

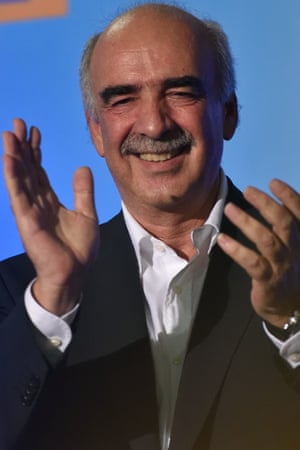

The key to Sunday’s election will be the behaviour of those disillusioned Syriza voters. Some seem drawn to the more radical left, some even to the far-right Golden Dawn (the most popular party among 18- to 24-year-olds). But plenty also seem willing to trust the back-to-stability image projected by New Democracy leader, Vangelis Meimarakis. At the very least, polls suggest, Syriza’s lead over New Democracy has shrunk dramatically. Some have had the two parties almost neck-and-neck.

The main political parties

Since the end of the military junta in 1974, elections in Greece have been dominated mainly by two political parties: the centre-right New Democracy and the socialist party Pasok.

In elections since 1981, the two parties combined won an average of 84% of the vote. That all changed with the collapse of the Greek economy and the bailout that followed. In the three elections since May 2012, the two parties’ combined score was 32%, 42% and 32.5% respectively.

Conversely, support for smaller parties has increased. Before the May 2012 election, support for the far-right Golden Dawn was less than 0.5%, and has always been above 5% since.

There are 19 parties and coalitions running in Sunday’s election. The parties most likely to comprise the next Greek parliament are:

- Syriza – the coalition of the radical left, led by outgoing prime minister Alexis Tsipras.

- New Democracy (ND) – a centre-right party and a member of the European People’s party grouping in the European parliament.

- Popular Unity – a far-left party formed by 25 MPs who broke away from Syriza.

- KKE – the Communist party of Greece.

- Pasok (Panhellenic Socialist Movement) – Greece’s socialist party. For the upcoming election, the party is in an electoral pact with Democratic Left (Dimar).

- To Potami – social democratic and liberal party founded in 2014 by journalist Stavros Theodorakis.

- Independent Greeks (Anel) - a rightwing party, the junior coalition partner in the outgoing Tsipras government.

- Golden Dawn – a far-right party.

- Union of Centrists – a centrist party founded in 1992. The party has never won seats in a general election, but it is polling around the threshold needed to enter parliament.

How will the election work?

About 9.8 million Greeks are eligible to vote and parties need to secure at least 3% of the vote to enter parliament for a four-year term.

The Greek parliament has 300 seats: 250 members of parliament are elected using proportional representation and the final 50 seats are automatically awarded to the party that wins the most votes.

MPs are elected from lists of party candidates in 56 geographical constituencies; voters in Athens, where half the population lives, elect 58 of the 300 deputies.

The share of the vote needed for a 151-seat majority will depend on how the overall result is divided between parties: if every party that runs actually gets into parliament, a 40% share would produce outright victory – but if lots of votes go to smaller parties that fail to clear the 3% entry barrier, the share needed for a majority drops.

Although voting is compulsory in Greece, it is not enforced. Turnout has dropped substantially over the past decade. In the 1980s it was consistently above 80%. In the 10 years to 2005 the average dropped to 75%. At the last election in January it was just under 64%.

In the event of no single party winning outright, President Prokopis Pavlopoulos will give the leader of the largest party a mandate to form a coalition. If that fails, the so-called exploratory mandate goes to the second party, then the third.

What do the polls say?

Based on these polling figures no single party is likely to win enough seats to form a majority government. Both the frontrunners, New Democracy and Syriza, would need to form a coalition with one or more of the other parties in order to govern.

Pasok, To Potami and the Union of Centrists would be the most likely junior coalition candidates. A coalition between New Democracy and Syriza is also an option, though Tsipras is not keen on it.

How can I find out more?

The Guardian will be covering the election in depth; all related coverage will behere. The paper’s Athens correspondent, Helena Smith, tweets at@HelenaSmithGDN. Nick Malkoutzis is founder of the authoritative Greek political and economic analysis website MacroPolis; he tweets at@NickMalkoutzis.

Malkoutzis is also deputy editor of the English language service of the Greek newspaper Kathimerini, which carries a round-up of the main election-related news stories here. The World Bank’s data and indicators for Greece can be foundhere. The latest IMF opinion on Greece can be found here.

Malkoutzis is also deputy editor of the English language service of the Greek newspaper Kathimerini, which carries a round-up of the main election-related news stories here. The World Bank’s data and indicators for Greece can be foundhere. The latest IMF opinion on Greece can be found here.

No comments:

Post a Comment